Here is one of the three main Bible passages used by many evangelicals in an attempt to shut down any idea of Christian universalism. Does it succeed in doing so? I don’t think so, but consider for yourself.

In flaming fire taking vengeance on those who do not know God, and on those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ. These shall be punished with everlasting destruction from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of His power. (2 Thessalonians 1:8-9 NKJV)

Here are several brief points I would note in response (and have done in discussions of this passage on Facebook).

The Fire

The fire of God is purgative. The God who is a “consuming fire” is the same as the God who is love. So, whatever the consuming fire of God is, it is always about love. God’s fire is a refiner’s fire (see Malachi 3; 1 Corinthians 3), not for the purpose of destruction, or retribution — God is love, and love is not retributive (see 1 Corinthians 13) — but for restoration.

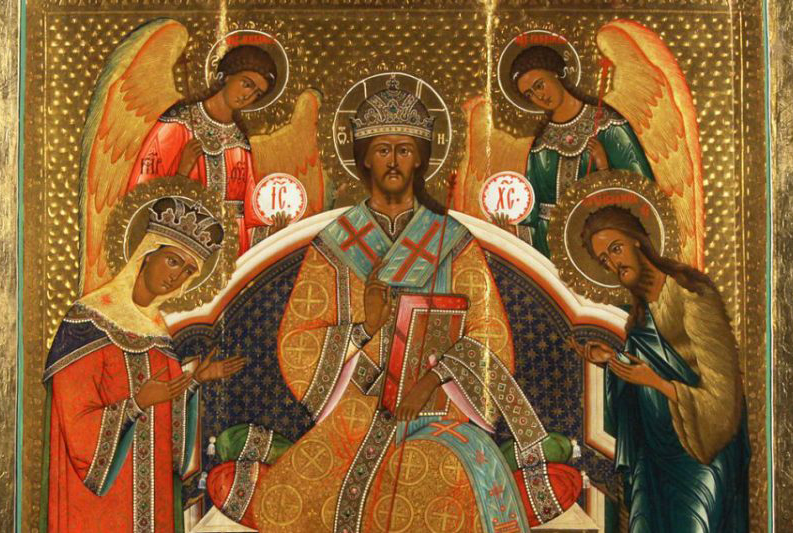

In Revelation 19:12, the eyes of Christ are like “flames of fire.” Nothing can be hidden from his penetrating gaze — he sees all. The flames are the consuming fire of God’s love, a refiner’s fire burning away all evil yet preserving in us what is good, what comes from God.

The Vengeance

The vengeance God metes out is not about retribution — for God is love, and love is not retributive. In Romans 12, Paul tells us about the “vengeance” of God. God does not repay evil with evil but with good; God overcomes evil with good.

The Punishment

The “punishment” is not retributive — God is love, and love is not retributive. The Greek word is tino and refers to a recompense. But again, Paul shows us in Romans 12 how God pays back: not with evil but with good; God overcomes evil with good. The vengeance and punishment of God are about chastening, for the purpose of correction and restoration.

The Duration

The Greek word translated as “everlasting” (or “eternal”) here is aionion and refers not to endless duration but to an age; generally, it is the age that is to come (and which is already breaking into this present age). The chastening punishment Paul speaks of here may be in the age to come, but it is not of endless duration. For chastening always has an end in view: the correction of an offender.

The Destruction

The “destruction” (Greek, olethros) itself is not endless. Nor it is retributive — God is love, and love is not retributive but corrective and restorative. In 1 Corinthians 5:5, Paul uses olethros concerning the man who was having sexual relations with his father’s: “Hand this man over to Satan for the destruction [olethros] of the flesh, so that his spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord.” The purpose of this was not the final destruction of the man but for his ultimate salvation and restoration.

The Presence

“From the presence of the Lord” does not mean that those undergoing such a terrible experience are shut out from the presence of the Lord. Quite the opposite, it is exactly the presence of the Lord — the overwhelming glory of God’s presence — that causes the distress felt by those who turn away from the love of God. They cannot escape the glorious, loving presence of God, yet they are unable to bear it — until the consuming fire of God’s love has burned away every wrong, dark thought about God that prevents them from seeing God as he truly is: self-giving, other-centered love, revealed in the crucified and risen Christ. There is one other place in the New Testament where we find the expression, “from the presence of the Lord,” and that is in Acts 3:20, where Peter says, “so that times of refreshing may come from the presence of the Lord.” It is not about being shut out from the presence of the Lord but, rather, what proceeds from the presence of the Lord.

See also From the Face of the Lord.

The icon form above is Christ of the Fiery Eye, from whose face nothing is hidden.