Every year at Christmastime the message comes to us in many forms — in sermons, banners, carols, greeting cards, even on bumper stickers: Jesus is the reason for the season!

From a Christian point of view the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ are at the center of time, for from Christ we look backward toward creation, the fall, the covenants, and God’s working in history to bring redemption. But from the event of Christ we also look forward to the fulfillment of history in the second coming of Christ. For this reason, time is understood from the Christian point of view in and through the redemptive presence of Jesus Christ in history. (Common Roots: A Call to Evangelical Maturity)

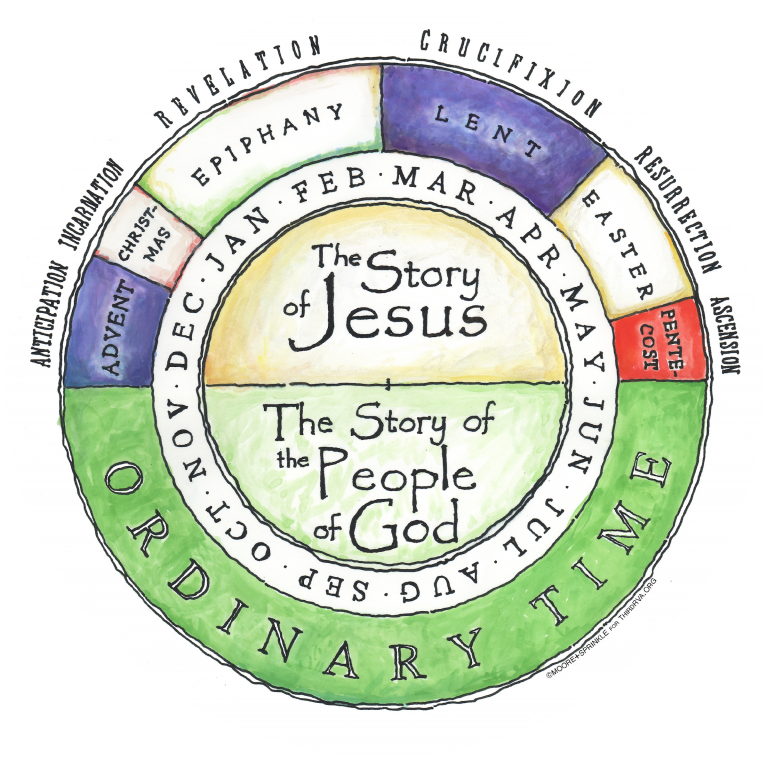

Some Christians know only two seasons of celebration in the Church: Christmas and Easter. Many do not bother with much in between. My daughter calls them “flower people” — they come only when the Church is decked out in Poinsettias or Easter lilies. But they miss out on something very wonderful, for the life of the Lord Jesus Christ in His Church is much richer than that — it is a full-time experience! The celebrations of the Church year, which have come down to us through the centuries, help us enter more fully into that experience, to know Jesus in all the seasons of life, and how each season flows into the next. So here is a brief summary of the Church year, submitted for your contemplation:

Advent

Advent means “coming.” The season of advent is a season of repentance and preparation — a place of beginning again. It is the start of the Church year and occupies the four weeks before Christmas. It is a time when we prepare to celebrate the coming of Christ, not only to a little stable in Bethlehem, but also His personal coming into our lives — “let every heart prepare Him room.” Hidden in the echoes of Advent we can also discern the promise of Jesus coming again to bring all things to divine completion.

Advent means “coming.” The season of advent is a season of repentance and preparation — a place of beginning again. It is the start of the Church year and occupies the four weeks before Christmas. It is a time when we prepare to celebrate the coming of Christ, not only to a little stable in Bethlehem, but also His personal coming into our lives — “let every heart prepare Him room.” Hidden in the echoes of Advent we can also discern the promise of Jesus coming again to bring all things to divine completion.

Christmas

There are twelve days in Christmas, beginning on December 25th and continuing through January 5th. In Christmas we celebrate the birth of Jesus; God incarnate; the Word made flesh. We think of the love of God and the saving work of Christ, for the Incarnation is as much a part of our redemption as are the Crucifixion and the Resurrection. Like the shepherds who received the announcement of the Christmas angels, we come to adore Him.

There are twelve days in Christmas, beginning on December 25th and continuing through January 5th. In Christmas we celebrate the birth of Jesus; God incarnate; the Word made flesh. We think of the love of God and the saving work of Christ, for the Incarnation is as much a part of our redemption as are the Crucifixion and the Resurrection. Like the shepherds who received the announcement of the Christmas angels, we come to adore Him.

Epiphany

Epiphany means “appearing” or “manifestation.” In this season, which begins on January 6th, we celebrate the ways Christ has made Himself known as the Messiah and Savior of the whole world, revealing Himself by many divine miracles and teachings. We think of the Babe made known to the wise men of the East; the Son made known at His baptism; Christ made known at the wedding feast in Cana. We also watch for the ways Jesus is making Himself known in the world today through His Church.

Epiphany means “appearing” or “manifestation.” In this season, which begins on January 6th, we celebrate the ways Christ has made Himself known as the Messiah and Savior of the whole world, revealing Himself by many divine miracles and teachings. We think of the Babe made known to the wise men of the East; the Son made known at His baptism; Christ made known at the wedding feast in Cana. We also watch for the ways Jesus is making Himself known in the world today through His Church.

Jesus is the “Light of the World.” In Advent, we celebrate the promise of the Light. In Christmas, we rejoice in the coming of the Light. In Epiphany, we wonder at the shining of the Light, just as the wise men marveled at the Star which led them to Jesus.

Lent

Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, six weeks before Easter Sunday. Like Advent, it is a time of repentance and preparation. The ashes on the first day of this season represent mourning over sin and the longing for holiness. In Lent, we remember the temptation of Christ in the wilderness and His journey to the Cross. We become aware of how Christ humbled Himself and how God calls us, also, to humility as we participate in His redemptive purposes. We consider, also, what our own place of service and sacrifice is in His divine plan.

Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, six weeks before Easter Sunday. Like Advent, it is a time of repentance and preparation. The ashes on the first day of this season represent mourning over sin and the longing for holiness. In Lent, we remember the temptation of Christ in the wilderness and His journey to the Cross. We become aware of how Christ humbled Himself and how God calls us, also, to humility as we participate in His redemptive purposes. We consider, also, what our own place of service and sacrifice is in His divine plan.

Lent concludes with Holy Week. On Palm Sunday, we think of the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, knowing that soon He would be rejected by the very ones who waved their branches and shouted Hosanna! The irony of this is subtly observed by the burning of this year’s palms to become next year’s Lenten ashes.

Holy Thursday commemorates the institution of the Lord’s Supper. It is also called Maundy Thursday because of the new commandment Jesus gave His disciples to love one another (maundy comes from an Old Latin term for “mandate” or “command”). On Good Friday, we think of Jesus on the Cross and behold the “Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.” Holy Saturday recalls how the world hung between death and life, sin and righteousness, darkness and light. It is a vigil for the Light.

Easter

In Easter we celebrate the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ — His victory over sin and death and all the works of the devil. A great exchange has taken place: Christ’s victory has become our victory, His life has become our life, and His righteousness has become our righteousness. Because of this, Easter is not just some “big Sunday” in the life of the Church. Rather, all other Sundays are little celebrations of this great Resurrection Day. The victory of Easter leads us on to the celebration of the Ascension, forty days later, when the Lord Jesus Christ ascended to His throne in heaven to rule and reign forever as King over all.

In Easter we celebrate the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ — His victory over sin and death and all the works of the devil. A great exchange has taken place: Christ’s victory has become our victory, His life has become our life, and His righteousness has become our righteousness. Because of this, Easter is not just some “big Sunday” in the life of the Church. Rather, all other Sundays are little celebrations of this great Resurrection Day. The victory of Easter leads us on to the celebration of the Ascension, forty days later, when the Lord Jesus Christ ascended to His throne in heaven to rule and reign forever as King over all.

Pentecost

Before He ascended into heaven, the Lord Jesus told His disciples to wait in Jerusalem for the “Promise of the Father” — the Holy Spirit. “You shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you,” Jesus said, “and you shall be witnesses to Me in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). That is exactly what happened ten days later, as we can see in Acts 2.

Pentecost is the commemoration of that event. It begins on the fiftieth day after Easter. In the season of Pentecost, we celebrate God’s gift of the Holy Spirit to His Church. The Spirit makes us one people, empowered to bear witness of the Lord Jesus Christ, to bring evidence — signs, wonders and miracles — of who Jesus is and what He has done for us.

Ordinary Time

After Pentecost, we move into Ordinary Time, the largest portion of the Church year. It reminds us that God most often comes into our lives in very ordinary ways and speaks to us in a “still, small voice.” When all of the feasting and singing and dancing give way to the tedium of work and the trials of life, God is still with us. The hope of joy is ever present in the silence and stillness of Ordinary Time, until it leads us once again to the preparations of the heart in Advent.

After Pentecost, we move into Ordinary Time, the largest portion of the Church year. It reminds us that God most often comes into our lives in very ordinary ways and speaks to us in a “still, small voice.” When all of the feasting and singing and dancing give way to the tedium of work and the trials of life, God is still with us. The hope of joy is ever present in the silence and stillness of Ordinary Time, until it leads us once again to the preparations of the heart in Advent.

There are, of course, many Scripture readings, symbols, themes, and even colors associated with these Church seasons, giving us a variety of ways to meditate on the person and work of the Lord Jesus Christ. Compared to the national traditions to which many Christians have become accustomed — Mother’s Day, Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, to name a few — these celebrations of the Church year seem like a radically new concept. But this perspective, although radical, is not really new at all. It is deeply ensconced within the traditions and history of the Church. It is a part of the heritage of every believer, a gift to us from those who have gone before. In it we receive a marvelous way to celebrate this new life we have in Jesus.

As you journey through your years, take up these celebrations of the Lord Jesus Christ. Let your heart always be preparing Him room. Rejoice that God came to dwell with you so that you might dwell with Him. Ponder how the Light of the World shines in all His glory. Consider His service and sacrifice, and how He invites you to partner with Him in the redemption of the world. Remember the Cross, and how it set you free. Dance in the wonder of His Resurrection victory. Drink deeply of the Holy Spirit and learn to walk in His power. Seek out the joy of His presence at every moment of your life, to recognize the quietness of His voice and the softness of His breath, and so let your heart be synchronized with His. Then you will know that, truly, Jesus is the reason for every season!

©2004 by Jeff Doles